|

|||

|

|||

|

|||

|

|||

|

|||

|

|||

|

The Jembe: basics and origin, arrangement, playing technique, rhythms, dance, handling, thighting jembes Also known as: le (he!) djembé (French), die Djembe (German), Yinbe or Yimbe (Malinke, Mali and Guineè), le papa (Guineè Conacry), Gbèlèkbè (Susu, Guineè), Sanbayi (Mali, Guineè).

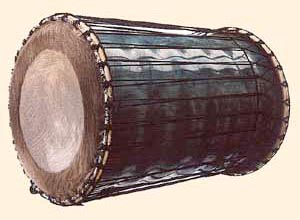

Basics and Origin The goblet-shaped drum, covered with the skin of goats or antelopes in former times, which today is generally known as jembe, has its origin in the peoples of the Malinke and Bambara in Western Africa. The Area today spreads over Guinea Conacry, Mali, Burkina Faso and the Ivory Coast.

Some authors suggest that the shape of the drum has oriental roots.

There is a historic but nonetheless still effective reason for the

spreading of this specific drum all over the world (notice the impressing

documentary "Djembefola" (master drummer) by one of the truly

greatest on this instrument, Guinea Conacry was the first French colony in Westafrica to declare independence; for this it was punished, the foreign nations isolated the newborn country. The notorious president Sékou Touré had the idea of founding National Ballets, formed of the very best artists, drummers and dancers of the country, to present his people and their culture to the white nations. Although somebody mourning over the end of the regime of Sékou Touré is hard to find, for in its last years it turned very authoritative and dictatorial, his idea was and is a great success.

The jembe today is the most common African drum in the western (industrial) world. (Practically any African ethnic group developed its own characteristic traditional drum, distinctive in shape, covering, sound and playing technique as well as in the rhythms produced on them: the sabar of the Wolof, the bougarabou of the Djola, the bata of the Yoruba, the ceramic udo of the Ibo in Nigeria, to mention just some examples of Western Africa.)

The shape of the jembe, the goblet, is an old spiritual symbol,

with, among others, the meaning of releasing oneself into the stream

of being). The wooden corpus is extremely durable but covered with

a relatively thin skin, which is played with bare hands. The direct

touch – skin to skin – can be felt. The rhythms played resemble a dance of the hands on the drum skin and may lead to a deep, meditative state. Listening, movement and feeling the skinny touch create a system of mutual dependence. [back to start]

The classic arrangement of the jembe The jembe is hardly ever played alone. The base drums let us make

out the rhythms in their totality, a fact often paid too less attention

to in the western world. The big djun (djung), the medium-sized

sangpan and the small kenkede (kenkene) are strongly covered with

thick cow skin. With relatively massive sticks (right hand) the

base-players draw dull, penetrating base rhythms from them, accompanied

by bells (left hand). Three to five jembe players (sitting) put

multivocal accompanying rhythms on this long bass-cycles that are

rhythmically "overflowed" by one to three jembe soloists (standing).

A wild interplay with the dancers is created; now and then one dares

to step into the centre of the ecstatic happening, showing a personal

interpretation The eruptions of rhythms are interluded by slower passages including songs of the griots. (Musicians are called griots in Western Africa. But griots are more than merely musicians, they are bearers of cultural knowledge. During feasts the guide the ceremonies, sing about people and their characters and stories with the aim to make them happy, more or less. Due to their power they have a questionable reputation in some ethnic groups, in others they are highly valued.)

"Real African music is so little known

that the European variety is often mistaken for authentic African

music - which in turn is too often taken to be a westernised toning

down of the real thing. In fact what we most often hear in Europe

is played by pseudo-African drummers who simplify everything and

perform the same regular monotonous rhythms, with neither creation

nor imagination. Such stereotyped rhythms have made us insensitive

– if indeed we in the west ever where respective – to

rhythmic subtlety. As soon as a rhythm becames too complex, our

sense shun it. We now recognise however that we have much to learn

on this subject in both Asia and Africa. For this reason, all our

composers and most of our best performers have started to study

Indian, Indonesian, Japanese or African rhythms. The

African drum is not an accompanying instrument. The African drum

is not a gong. The African drum is not exotic. The jembe does not

provide fun for the tourists nor is it part of a variety act, nor

is it a "bit of local colour". It is an INSTRUMENT."

The beats of the jembe are rich in overtones. Even beginners are quickly able to produce pleasing sounds, naturally depending on enough practice and good teachers. The most important beating techniques (sounds) are: bass, open sound (tone), slap and tap (dip). More rarely used effects are: muffled bass, muffled slap. Moreover, the borders of creating different sounds are only set by imagination. The sounds in detail: The bass-beat is played with the outstretched flat hand in the middle of the drum skin. The skin bounces back the hand and is able to swing freely. Very small jembes may produce the best bass-sounds with the anterior finger-joints beaten on the middle of the drum skin; actually this is the technique for the muffled bass, leaving the hand on the skin. Such a beat is frequently followed by a muffled slap, played while the bass-hand is still lying on the skin. Because of the differentiated coordination of time and movement inside a rhythm, this is considered an advanced technique. The open sound (dark, tone, sombre): This beat is played on the outer rim, about one third from the edge to the centre. The finger-joints produce a full sound, whereas the anterior edge of the palm touches the edge of the jembe. The sound should be dry, not piercing, resembling raindrops on a tent. The character of the sound is defined by the time the hand is in contact with the drum skin. The shorter, the more piercing, the longer (tenths of a second), the dryer is the sound. Smaller drums once again ask for a slightly different hand-position, otherwise the outcome is a bass. The slap (snap, light, claire, claqué) is the most difficult beat for beginners. Later on, however, one might notice that well played, loud and dry open sounds (tones) are the bigger hurdle to overcome. For the slap the palm beats on the edge of the drum (attention: blisters, even broken bones occur). In doing this, the fingers should have enough tension to elastically hit the skin like the tip of a whip. A light, high-pitched, sometimes cracky sound rich in overtones is produced. The real skill lies in making this sound softly as well. Slap and tone should mark the different ends of possible sounds. Modulations in between are possible, according to the rhythm. The slap asks for a lot of practice and is seldom reached through self-training alone. Anyway, there are plenty of workshops at any level available and the number of qualified jembe-teachers is steadily growing all over Europe. The tap (dip) is actually a stopgap while playing "hand-to-hand": In the breaks the fingertips dip on the edge of the jembe, to keep in rhythm. In Africa, this technique is almost uniquely used by soloists accompanying themselves with songs. The jembe is a hand-drum. The playing technique is easily learned, compared to other instruments – no enduring practice is necessary to produce her typical sound, rich in overtones and broad scaled in frequency. Congas, bougarabous, the sabar or the Indian tablas, e.g., present a much more complex playing technique and are therefore more difficult to learn. This leads to a frequent underestimation: The jembe, like any other instrument, asks for precision regarding rhythm and timing. There is not much sense in "tricking" this musical necessities

with arguments like: "its spontaneous creativity" or "beating

the drum has to come out of the belly" or "I am led by my own,

inner rhythm" or "the point is the esoteric training of the

consciousness". Arguments like this may, standing for themselves,

fit into some sort of situation.

Workshop 2003 in Kleinmühl Hand-to-hand vs. freehand Europeansn as beginners mostly prefer the so called "hand-to-hand" playing technique. In this a steady left-right-movement is kept up, breaks are indicated by silent fingertips on the edge of the jembe. The beats are executed by the appropriate hand – the proper technique for beginners. It helps to reach continuity in the play, count and time the breaks and bridge over them, respectively, and makes it easier to set notations into practice. Coming to double beats, fast passages or triples, this technique is no longer working satisfyingly – left hand and right hand have to become independent from each other. This leads to the so called freehand-style, usual in Africa, which means that the beats are economically distributed on both hands, regardless of any steady left-right-movement. But now enough of the theory, this all can be learned in workshops at any level of skill. [back to start] Types, covering and qualities of the jembe I now give you some tricks right from my workshop and some experiences of the countries of origin of the jembe, thus helping you to distinct criteria of quality of the drum and find your ideal jembe.

In industrialized countries bodies are also made of glass fibre, produced as cooper work or turned out of the lathe from solid wood or glued wood. Other materials are possible – e.g., from my workshop out of Hempstone R , a fascinating, absolutely ecological material based on a cellulose fibre compound, bounded with water. In the last years the trees for jembes became rear because of overexplioting. The proportions of kettle and funnel are slightly variable. Drums with smaller kettles produce a sharper sound, bigger kettles and slightly thicker goatskin covering accentuate the bass tones.

According to the shape the African jembes carry a variety of names. If the funnel is curved, the drum is called jembe bara, jembé soulé indicates a straight pipe. The diameter of the narrowing between kettle and funnel or pipe mainly determines the height of the bass tone. The smaller this opening, the deeper sounds the bass – too small narrowings allow only a faint and dull tone. The well shaped and smoothly carved body of the drum is covered one-sided with goatskin. In Europe thicker skins are sometimes used – from stag, calve or he-goat. According to my experience this is nonsense, because the physical shape of the jembe allows an extremely high scale of tones, but not with skins too thick. It´s like putting the engine of a Volkswagen into a Porsche. Thick skin fits to drums with big kettles, like congas or bougarabous, where it´s able to show its distinct type of sound. At the narrowing of kettle and funnel (or pipe) an iron ring of a least 6 mm strength is welded tightly. It may be covered with fabric. Then a rope of 5 or 6 mm is laid into several loops, depending on the actual number needed. Beware of trying to save money at this step! Ropes less than 5 mm strong stretch or may even tear. A general rule says that the number of loops should equal the diameter of the jembe in centimetres – that is, 36 cm need 36 loops. Less loops I would call a scanty cording.

For the covering the soaked skin is laid over the body of the drum. A prefabricated iron ring (should fit tightly, also a criterion of quality) is put over it and the skin is folded inwards. A second iron ring, covered with fabric, is corded with as many loops as given by the lower ring and put over the infolded skin. Now its time for zigzagging the tether through the loops of the upper and lower ring. It´s important to use one piece of rope for that with an extra length of at least 1 metre. Round the drum the tether is stretched until the covering has a little tension. After drying the skin the rope is stretched again, then the skin can be shaved if necessary and the parts jutting out be cut off. The loose end of the tether is now used for the cross cording. Therefore you put the loose rope under one of the "vertical" ropes and then under the one "behind" it, that is the left if you work left to right, the right if you work right to left. The two wounded "vertical" ropes are now forced together by pulling the tether, thus further increasing the tension of the covering. Mind that you should always pull downwards to prevent the cross cording rope from wandering to the upper ring.

The cording is exhausting and therefore one of the most important steps in the process to save time and/or material. The different qualities of the cording have influence on the durability and the climatic sensitiveness of the covering skin. Our jembes show tightly fitting rings which allows increasing the tension easily afterwards. As a test you play some strong bass beats. If the tone deepens, you have to reinforce the cording. The more loops you used, the better the tension can be divided evenly which leaves some elasticity for the skin to shrink in dry heat and get looser in wet cold. Thus the skin is protected from over-tensioning and frequently reinforcing the cording is unnecessary.

In my opinion the quality of the work is important. Don´t decide just because of optical impressions. The body should be free of cracks. If not, the drum is not ultimately useless; the cracks have to be cemented to prevent air from coming out of the body, producing a bad bass sound. Epoxy resin and wood-dust proved an ideal mixture, normal white glue is less recommendable. The body should be made from hard wood (HempstoneR is more harder). The skin, due to the shaving or rest of hair, might be a little rough in the beginning. It´s smoothed while playing. If you do not want to leave all the work to your hands, you can use very (!) fine sand-paper first or better a raiser blade to scratch(careful at the edge). If you cream your playing hands (e.g. shea-butter, do not use any light or moistening creams), the skin by time gets a very fine, water-resistant surface. [back to start] The "right" jembe, look also: a fine jembe should....

The right size: If you´re looking for an ideal jembe for practicing, you choose one that you are able to play in a comfortable, upright sitting position without bending the wrists too much; the jembe is tilted forward slightly. Big concert drums, slung around your body with belts, can be played standing or sitting on a higher seat. Very small jembes demand a different playing technique, which makes them inadequate for practicing or beginners. Drummers always have a selection of well-treated, ready-to-play jembes at hand – for different occasions, because of the different sounds or as a reserve in case a skin tears (it needs some time to cover the drum freshly and accurately tune the new skin). [back to start] In Africa, dance and rhythm are part of the same, strongly woven and mutual system. The dancers move to the drum as well as the drummers try to interpret and enforce the individual style of the dancers. The rhythms of Western Africa show some typical signs: The counting cycle is most often 12 beats or a multiple of it. Some authors speak of ternary four-four-times. The dance-steps mostly follow the fourth symmetrically, the fourth are divided three times, that is ternary; altogether this counts to 12 beats for a common time. In my experience dance is not reduced to the legs only, in Africa the whole body dances and ternary patterns of movement can be noticed in shoulders, arms, hands etc. as well. Just have a look on a dancer, doing one of the multiple (about 20) doudounba-rhythms.

Counting to three, counting to four – some rhythms are grooving somewhere in between and refuse to fit into a general scheme. Inside the pieces one can find introductions (intros), rhythmical calls and blocks (apell, blockage, break), compressions with upspeedings (chauffer), which are altogether fixed as signals inside any dance and rhythm. The rhythms are definitely identifiable by the base-voices, mostly multiples of the jembe-rhythms, better than by the accompanying jembe-voices, which can be the same or similar through a variety of rhythms and dances. You now understand that this music does underlie a mathematical system, although it´s not always clearly shown to our eyes: calculated feeling. If I managed it to wake your interest in the world of rhythms and drums, all these lines have fulfilled their purpose. [back to start] © 2000-2003 Norbert Schmid | DRUMPARAM | Kleinmühl

| A-3970 Weitra |

||||||||||||||||||||||||

Händler und Partner DrumParam

ist autorisierter Händler von Schlagwerk-Percussion.

Informieren Sie sich über Shea Butter als

Pflegemittel.

The

body of the jembe is usually carved out of a single tree-trunk

and is composed of a kettle and a tube or funnel. For the production,

different kinds of wood are used in each African region.

The tools are simple, but proper shaped carving-irons, pickaxes

and big rasps. A skilful carver may shape a raw body in 4 to

6 hours.

The

body of the jembe is usually carved out of a single tree-trunk

and is composed of a kettle and a tube or funnel. For the production,

different kinds of wood are used in each African region.

The tools are simple, but proper shaped carving-irons, pickaxes

and big rasps. A skilful carver may shape a raw body in 4 to

6 hours. In

Guinea and the tropical regions in general the drum-carvers prefer

to use silk-cotton, khari, wulinyi, ngoni and often the highly demanded

longai (lingue, afcelia), that is, tropical woods in the majority.

Also cheap, quickly shapeable woods of the balsa-type are used.

Although the side of such drums comes out rather thick, some of

them produce a sound not too bad. In Senegal and the Gambia, dry

savannah regions, Duto (wild mango tree, cordilla pinnata)

is mostly used – an extremely durable wood with excellent acoustic

properties. The carvers prefer the wood of naturally died trees

or in bushfire died trees, which is almost free of cracks.

In

Guinea and the tropical regions in general the drum-carvers prefer

to use silk-cotton, khari, wulinyi, ngoni and often the highly demanded

longai (lingue, afcelia), that is, tropical woods in the majority.

Also cheap, quickly shapeable woods of the balsa-type are used.

Although the side of such drums comes out rather thick, some of

them produce a sound not too bad. In Senegal and the Gambia, dry

savannah regions, Duto (wild mango tree, cordilla pinnata)

is mostly used – an extremely durable wood with excellent acoustic

properties. The carvers prefer the wood of naturally died trees

or in bushfire died trees, which is almost free of cracks.

Rhythms

and dances

Rhythms

and dances  Besides,

some actual binary rhythms can be found, that is structures that

count to 8, 16 or 32: kuku, kassa, djole, zaoulia, djagbe,

könö and others (the yankadi is considered binary or ternary,

according to the author). I also know about western African rhythmical

structures counting to 18 (njandufare, kokobasajo); the four-four-times-structure

can´t be generalized. I see another reason for not doing this,

because it highlights the problem: We, the Europeans, need schemes,

patterns, letters – we want to understand. An African bearer

of cultural traditions doesn´t care at all about such things.

What is transported from one generation to another is a "feeling".

Sometimes it´s altered, changes occur, it´s alive. That´s

what makes the whole topic so interesting. That is the reason for

so many different spellings of the names, the different notations,

the different interpretations according to our musical schemes.

Besides,

some actual binary rhythms can be found, that is structures that

count to 8, 16 or 32: kuku, kassa, djole, zaoulia, djagbe,

könö and others (the yankadi is considered binary or ternary,

according to the author). I also know about western African rhythmical

structures counting to 18 (njandufare, kokobasajo); the four-four-times-structure

can´t be generalized. I see another reason for not doing this,

because it highlights the problem: We, the Europeans, need schemes,

patterns, letters – we want to understand. An African bearer

of cultural traditions doesn´t care at all about such things.

What is transported from one generation to another is a "feeling".

Sometimes it´s altered, changes occur, it´s alive. That´s

what makes the whole topic so interesting. That is the reason for

so many different spellings of the names, the different notations,

the different interpretations according to our musical schemes.